I remember in college overhearing bits of one of “those conversations,” one of those times someone had done a reading for class that tickled them just so, where a professor had made a comment that agitated them just right, where something about the intellectual gears of college were clicking to spur some big thinking. This friend was remarking to another person, “Did you realize that our prayer isn’t to change God’s mind but to help us change ours?” I wasn’t party to the rest of the conversation, but the essential question was enough to whet my appetite.

That sort of realization makes sense, as I think a natural way to conceptualize prayer, at least as one grows up and first learns their faith, is as a list of requests one makes of God. After memorizing my basic prayers as a little guy, the first insight on prayer I remember learning was from my 2nd grade teacher, Mrs. Johnson, who prepared me for First Communion. She taught us that, after we received communion, it was good to follow up with prayer. Her recommendation was to “thank and ask” -- share one thing with God for which you’re grateful and ask God for think you need. In retrospect, some solid foundational prayer habits to teach eight-year-olds, let alone an adult!

Branching out a bit, theology and catechesis teach us that there’s four basic areas of prayer: praise of God, petition (what we need), intercession (what others need), and thanksgiving. Hopefully, as one’s faith life widens and deepens, one gets exposed to various mediums of prayer, too: sacred music, Taize prayer, centering prayer, contemplative prayer, the Liturgy of the Hours, Eucharistic Adoration, interfaith and ecumenical prayer and prayer services, the Rosary and novenas, and so much more. But even as I grew up and enjoyed the diversity of prayer and liturgical formation, I still don’t think I evolved on my understanding of prayer’s underlying purposes until well after rolling all of these experiences into my spirituality.

One of the major takeaways from my brief foray into spiritual direction during college -- a few years after the aforementioned overheard conversation -- was a bit of a course correction on my attitude toward prayer. First of all, my spiritual director affirmed my desire to pray for loved ones and for their intentions, but he felt my desire to cover those areas so comprehensively was preempting me from going anywhere deeper in my prayer; he suggested that, at least sometimes, I simply take a deep breath and acknowledge that God knows all these intentions in my heart. There’s certainly value in naming these people and intentions, but acknowledging that I was spinning my wheels at times helped focus my prayer time more deeply. Secondly, he encouraged me to focus less on the outline or agenda I carried into prayer and more on making space. Rather than figuring out what I wanted to say to God, I needed to prioritize quieting myself to listen for what God wants to say to me.

These revisions to my prayer discipline helped emphasize the “thy will be done” element of prayer in a new way. Not only do my prayers need to be contextualized in the will of God, but I also need to remix my whole approach such that my priority becomes more specifically listening for what God’s will for me is. I am always struggling to keep this adjusted approach in mind and use it effectively, but the broader impact has stuck with me.

Previously, I came to God trying to share myself. God already knows me and my wants and needs. I almost imagine it like the difference between small-talk and a good, deep, heart-to-heart conversation. God is happy to see me and hear from me, but He doesn’t want to spend most of the time talking about the weather. God wants to shine His light deep into my heart and help me learn the innermost workings of who He made me to be. Not easy, but certainly appealing and inviting!

In my adult life, I’ve found myself gravitating more and more to the lives of the saints. I haven’t gained an encyclopedic knowledge of them or memorized too many feast days. Rather, I’ve organically found attraction and resonance with the witness of the martyrs and their connection to us as friends and intercessors.

While I don’t think we are all called to the crown of martyrdom, I think the essential nature of their lives is their witness. Their ultimate sacrifice of love in Christ came from their fundamental desire and decision to give themselves entirely to God and die to themselves. Saint Oscar Romero discarded his hesitations over stepping on toes and ruffling feathers and instead committed his whole influence and person to the needs of the Salvadoran campesinos, even as it invited inevitable retribution on his life; Saint Maximilian Kolbe held fast to his faith as a terminal prisoner in a concentration camp, diligently working, oversharing his rations with weaker prisoners, and ultimately offering his life for that of another in the ultimate act of charity; Saint Charles Lwanga and his companions clung to their budding faith even as their king became lustful, violent, and capricious, remaining faithful even as they were dragged to the flames of death; Saint Lucy and many other early female saints insisted on their chastity and spiritual prioritization of Christ above any arranged marriages or coercion to become wives to men; and the list can go on and on.

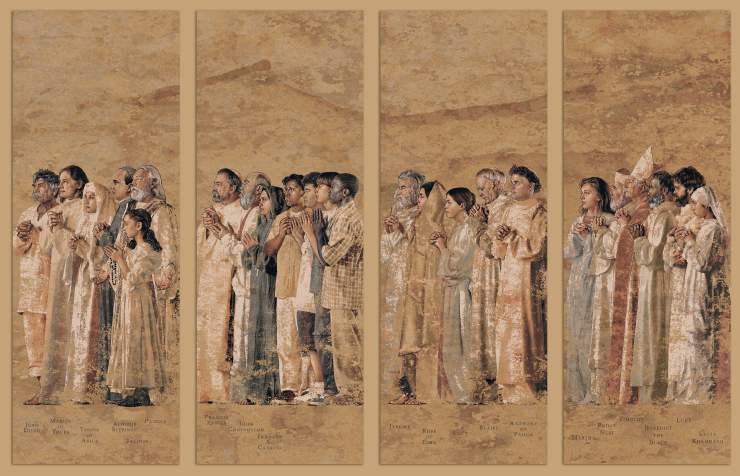

|

| The communion of saints, as depicted in the tapestries at the Los Angeles Cathedral |

While the stories around their deaths, their relics, and their miracles can certainly captivate, it’s the more mundane witness of their living that draws me in. In Oscar, I find a person who realized the need to stop making excuses and compromises that constrained his faith; in Maximilian, I find a person who wouldn’t discard his Christian hope in the face of any threat or mistreatment. It’s that all-encompassing centrality of faith that draws me to them and their intercession. The gritty realities of their life make them accessible, and the grand witness of their faith show us what is possible in ourselves.

So as I think about how prayer isn’t just us trying to ask God to do stuff for us, I imagine my intercessors less as errand-runners carrying messages to God. Instead, I’m growing to see them more as a third person in my conversation of prayer. As I contemplate my lack of patience with my daughter, my frustrations that I don’t have more time to do what I want, my struggles to juggle the various practical and social-emotional needs of my family, who better to join me in my prayer than my martyrs. Oscar, Max, and the bunch gave their lives as witness to the power our love gains when we humbly die to ourselves and live more fully in and for Christ. In prayer, I invite them and their witness close to me so that I can be palpably reminded me not only of the power of humility, of humbly being Christ’s love, but also of its very real and reachable feasibility.

So as I think about how prayer isn’t just us trying to ask God to do stuff for us, I imagine my intercessors less as errand-runners carrying messages to God. Instead, I’m growing to see them more as a third person in my conversation of prayer. As I contemplate my lack of patience with my daughter, my frustrations that I don’t have more time to do what I want, my struggles to juggle the various practical and social-emotional needs of my family, who better to join me in my prayer than my martyrs. Oscar, Max, and the bunch gave their lives as witness to the power our love gains when we humbly die to ourselves and live more fully in and for Christ. In prayer, I invite them and their witness close to me so that I can be palpably reminded me not only of the power of humility, of humbly being Christ’s love, but also of its very real and reachable feasibility.

No comments:

Post a Comment